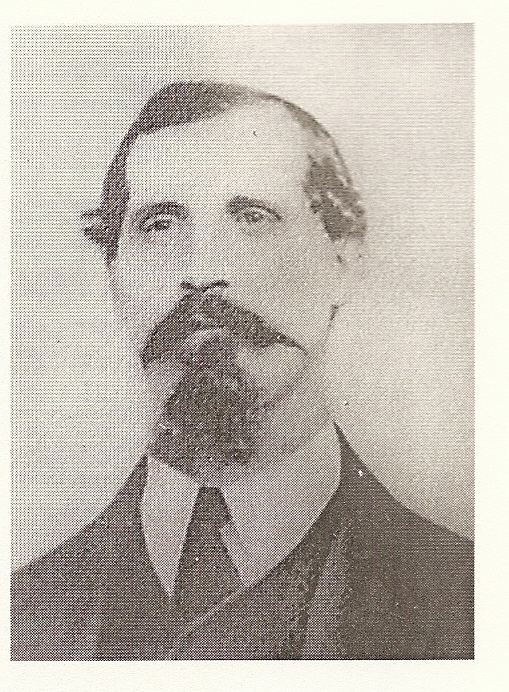

Romulus Moore represented Columbia County in eastern Georgia in the 1868 Assembly. Columbia County was created in 1790 from neighboring Richmond County, home to Augusta. Fellow Original 33 representative, Thomas Beard, represented Richmond County just to the south.

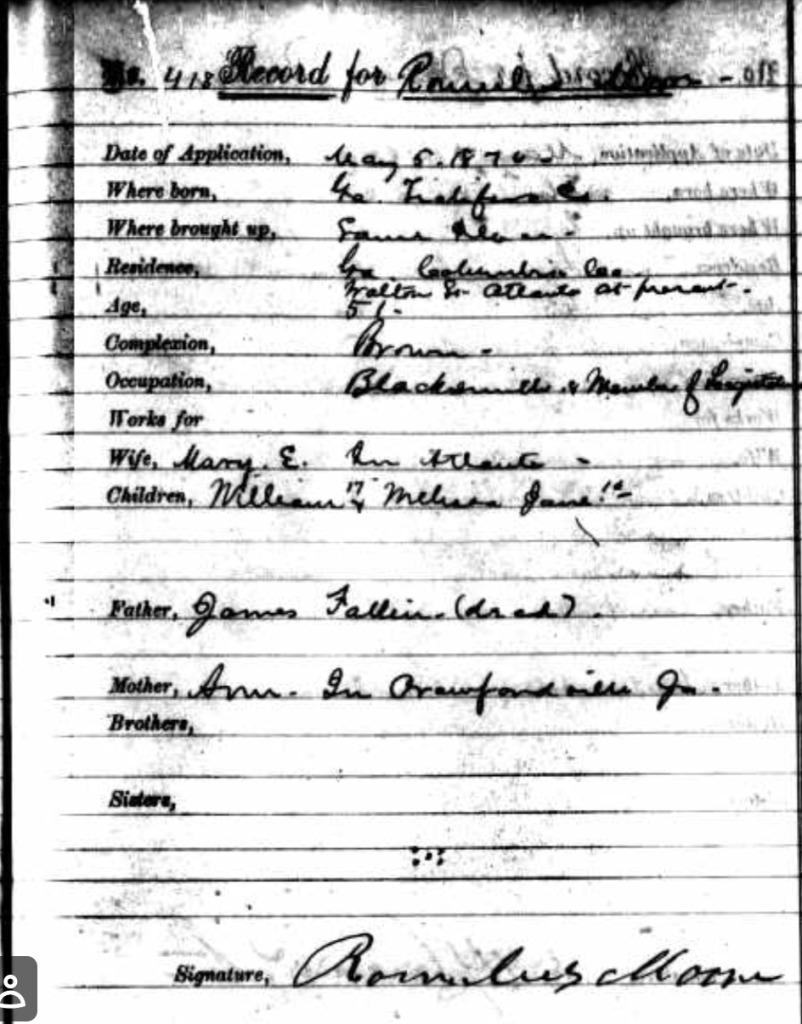

Moore was born into slavery in Taliaferro County, Georgia in January 1818, which is located two counties west of Columbia County and holds the birth home of Alexander Stephens, vice president of the Confederacy. Moore grew up in the household of James Wellborn Moore and his wife Sarah and was educated alongside the white Moore children. Moore was a wealthy farmer who owned 10 enslaved people in 1840 with real estate holdings of $2500 in 1850.

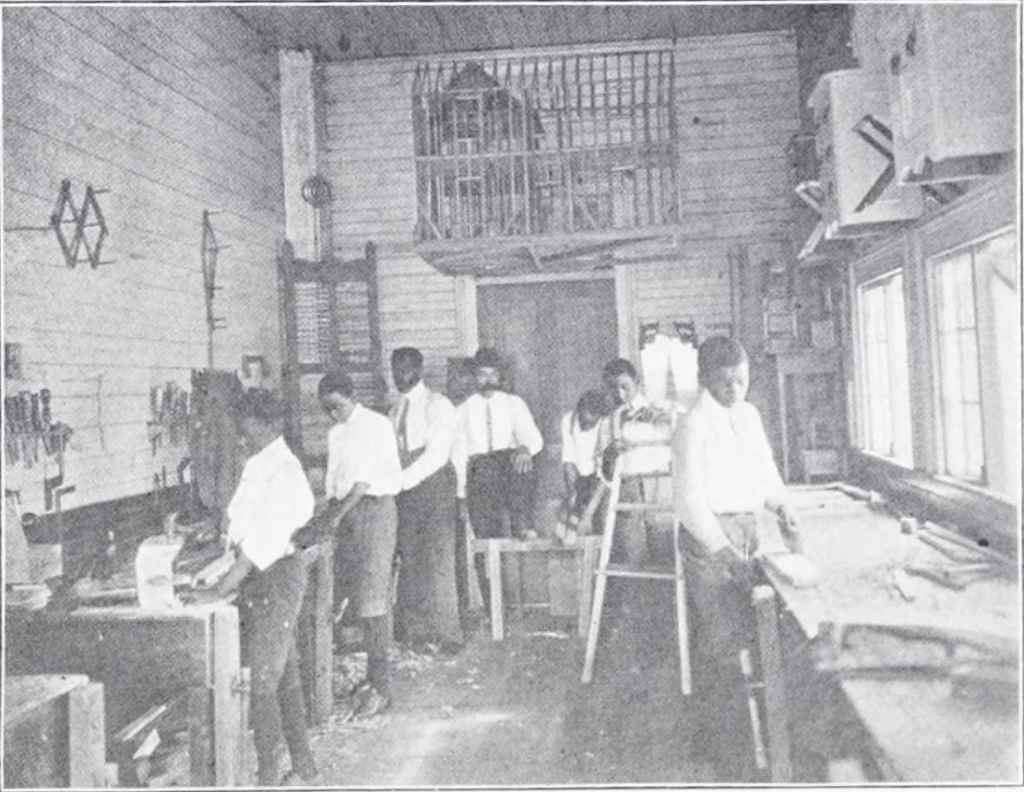

Moore was a trained blacksmith as well as a Baptist minister, and he was able to purchase his own freedom years before the start of the Civil War. Moore married Mary Elenor Horton in 1860 and joined the First Baptist Church of Thomson, Georgia. In 1867, Moore was ordained to the gospel ministry by the Rev. Henry Johnson, of Augusta, GA, and accepted a position as pastor at the Poplar Head Baptist Church in Columbia County. That same year, Moore also entered politics as a federal registrar in 1867.

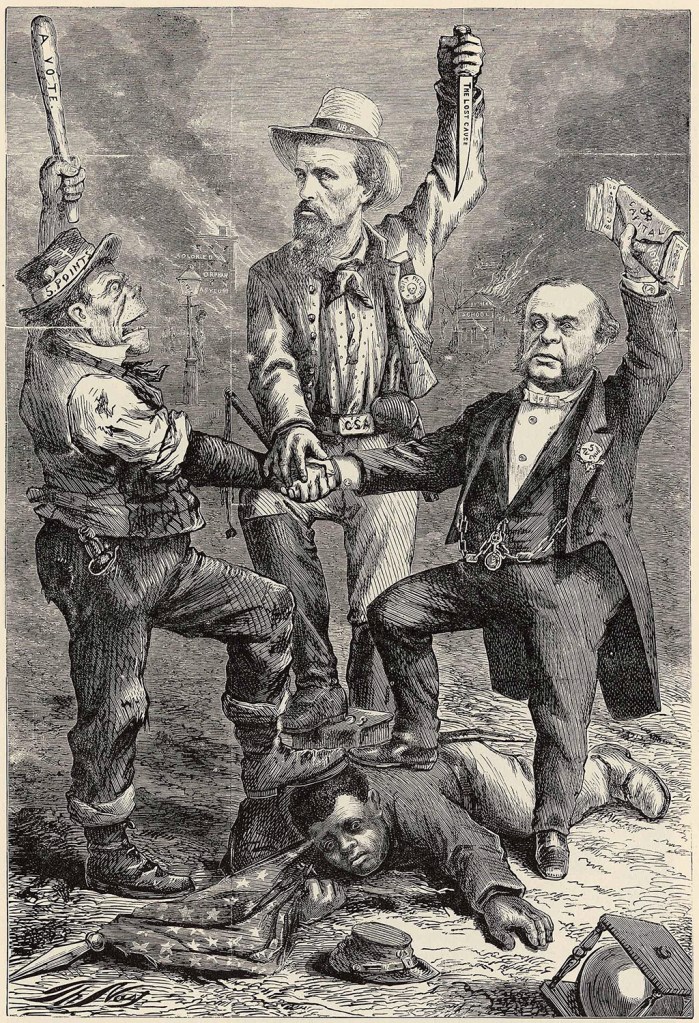

Like many of his fellow Black legislators, Moore served in the Constitutional Convention of 1868 and was active in various facets of Georgia politics. Moore believed in separatism and, in the 1870 Assembly proposed that newly freed Black Americans wouldn’t find justice living among whites and should move west to form their own community. His colleague, Tunis Campbell, who had belonged to and then fought against the American Colonization Society, an organization committed to Black resettlement in the Colony of Liberia, was ardently opposed to Moore’s recommendation. The Assembly delegates chose to not move forward with his emigration proposal and sent it back to committee.

Romulus Moore remained a colleague and friend of Tunis Campbell during his 1875 indictment and arrest for the false imprisonment of Isaac Rafe, a white man whom Campbell charged with breaking into Black family homes and abusive behavior while Campbell was serving as Justice of the Peace in McIntosh County. Many White Georgians had been looking for an opportunity to arrest Campbell, given his power in Georgia Politics, and Campbell denied both charges and evidence. After his arrest while on his way from Milledgeville to a convict labor camp in the Dade County coal mines, Campbell was kept in custody for one night at the Fulton County jail. Romulus Moore, now a boarding housekeeper in Atlanta, hired W.F Wright and D. P. Hill to represent Campbell and secure a writ of habeas corpus. Campbell appeared before Judge Pittman in Fulton County and denied his lawyer’s requests to change the venue of his case to the U.S. Superior Court. Campbell did end up spending 1-year sentences to hard labor and, upon his release, left Georgia for New York.

In 1874, Moore attended the Colored Convention as one of approximately 60 delegates. He continued to support Black emigration from Georgia to the West to find freedom and equality in Black settlements along with his former Assemblyman colleague, Reverend Henry McNeal Turner. Turner supported Black emigration out of Georgia, but even further than the western states (Texas, Louisiana, Arkansas) that Moore suggested: “Whatever the condition of the negro to the other states, it will ultimately be his condition in Georgia. Providence is shaping their destiny and not blind chance. They are not to be more in one state than another.” He proposed the US Government give freed Black Americans a colony in New Mexico accompanied by “transportation and rations for size months.” This would enable Black Americans to establish their own communities and “get credit for what they did.” Turner ultimately supported a return to Africa, which would be the only way he saw for Black Americans to have free and independent lives. Turner founded the Migration Society and organized two ships with 500 emigrants to travel to Liberia in the mid-1890s.

Moore passed away at his home in Georgia sometime before 1888. In addition to being one of the founding fathers of the 1865-1896 Civil Rights movement, Moore was one of the founding leaders of the Black Baptist Church in Georgia, which is the largest African-American religious group in the state.

REFERENCES:

References:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Romulus_Moore

James Wellborn Moore https://www.wikitree.com/wiki/Moore-14585

James Wellborn Find-A-Grave https://www.ancestry.com/discoveryui-content/view/120341754:60525?tid=&pid=&queryId=85c258761c2ae3c939264b1b07b6122f&_phsrc=fRj32&_phstart=successSource

1840 Census: https://www.ancestry.com/discoveryui-content/view/1848000:8057

“The Colored Convention” Dec 1 1874

https://www.newspapers.com/image/26778206/?terms=%22Romulus%20Moore%22%20&match=1

James Fallin, 1870 Freedman’s Bank Records https://www.ancestry.com/search/collections/8755/records/60184909