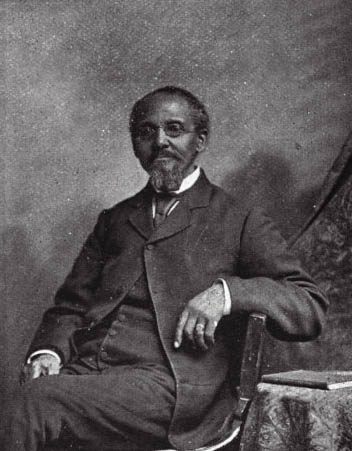

James Merilus Simms was born December 27, 1823, and enslaved at James Potter’s Coleraine Plantation, located upriver from Savannah, Georgia. It’s implied that he was the son of his enslaver, and learned to read and write from the tutor that Potter hired for his white children. In 1857, either Sims or his mother (accounts vary) purchased his freedom. He was baptized into the First African Baptist Church of Savannah, later expelled for lack of humility, and returned in 1858. By 1860, Sims had become an ordained minister and was operating a school for Black children in Savannah. Only six schools of this kind existed in antebellum Savannah, as educating Black people was considered a crime. Simms was the only teacher punished for this crime and was sentenced to a fine of $50 and fifteen lashes. Shortly thereafter, he moved to Boston, Massachusetts, where his younger brother had moved after escaping enslavement in 1851.

Simms joined the Union Army, serving as chaplain during the Civil War, and by the spring of 1865, he was back in Savannah. In 1867, he established the Southern Radical and Freedman’s Journal (later renamed the Freeman’s Standard). He also worked for the Freedmen’s Bureau and was a Union League organizer. Sims was one of the ministers to sign a petition protesting the treatment of Black soldiers in the Union Army and was an ardent supporter of voting rights.

He wrote The First Colored Baptist Church in North America, which entailed the history of First Bryan Baptist Church, and he is credited with establishing the first Prince Hall Masonic Lodge in Georgia. Simms was elected to the Georgia House of Representatives in 1868. After being expelled, he was reinstated in 1870 but subsequently lost re-election.

In one of Governor Rufus Bullock‘s last acts before he left office, he appointed James Simms, district judge of the First Senatorial District sitting in Savannah, the first Black judge in Georgia. New Democratic legislators moved the court out of the district. Afterward, Simms received a federal appointment as inspector at the U.S. Customs House in Savannah. He remained active as a senior statesman in the city’s African-American community until his death on July 9, 1912. The Most Worshipful Prince Hall Grand Lodge of Georgia placed a monument over Simms’ grave in Laurel Grove South Cemetery in June 1920.