On Saturday, September 19, 1868, peaceful African-American marchers were threatened, beaten, tortured, and murdered in Camilla, Georgia, in what would become known as the Camilla Massacre. Over weeks of violence and terror, between nine and fifteen individuals lost their lives, and at least forty were wounded.

Leading up to the Massacre

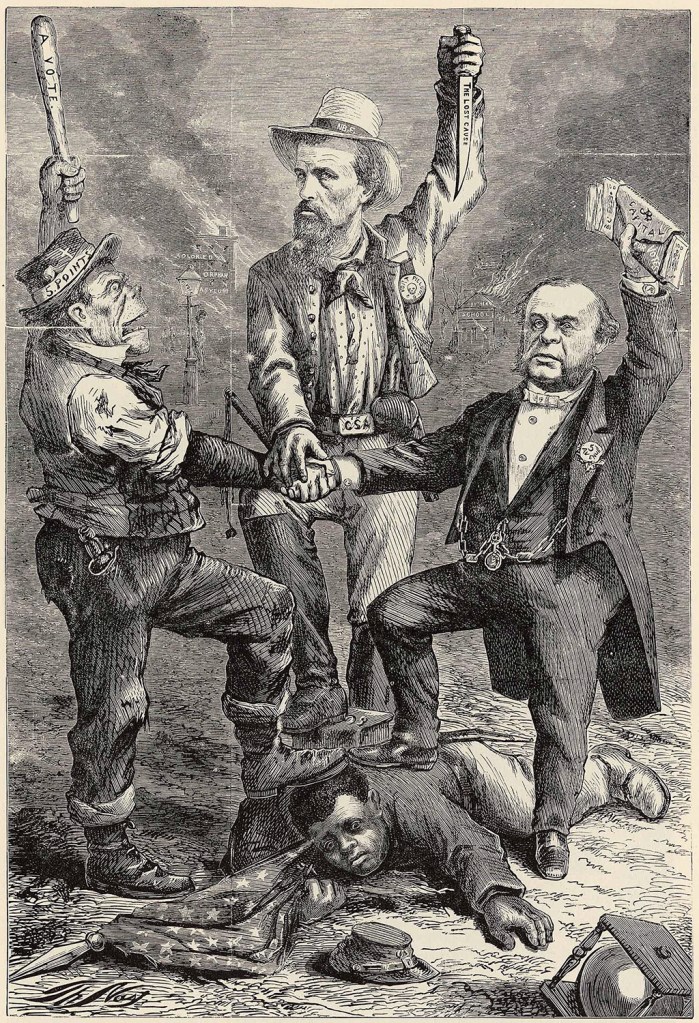

The violence and killing by white Georgians during the Camilla Massacre was by no means an isolated occurrence despite some newspaper reports that cast the event as an anomaly. For the three years following the Civil War, white Georgians had attacked freedmen and republicans with little government intervention during Union occupation. This oversight perpetuated the strategy of enacting violence against Black activities as a legitimate strategy to keep former slaves in line with White Supremacy. While Black Georgians had earned the right to vote in Georgia’s 1868 Constitutional Convention passed the previous April, white Georgians used violence and quazi-clandestine organizations like the Ku Klux Klan to intimidate, suppress and disenfranchise African Americans in the ensuing months. Nonetheless, 33 Black Assemblymen persevered against threats of violence and voter intimidation and were elected to the Georgia House of Representatives and Senate only to be expelled from the Assembly by white legislators in early September 1868. Many events of white violence occurred at campaign events, Republican party events, and voter rights and registration events.

In protest of the unlawful expulsion, Black Assemblyman Philip Joiner (Rep- Dougherty County) led a 25-mile march from Albany to Camilla. This Mitchell County seat included several hundred Black Georgians (freemen) and a handful of white Georgians to attend a Republican political rally on the courthouse square. The violence that they met, while the largest in scale, was not uncommon in southwest Georgia at the time. These events demonstrated that during 1868, white citizens in southwest Georgia openly and frequently attacked freemen without repercussions. Repeated smaller attacks were met with no response from local authorities. Authorities refused to investigate, let alone prosecute, whites for attacking Black Georgians, further empowering the level, frequency, and brazenness of violence that whites could easily get away with.

Details of the Camilla Massacre

Black freedmen traveled from neighboring counties, including Dougherty, the most populous county of Black Georgians in southwest Georgia. Many were coming to hear Republicans William Pierce and John Murphy. Whites in the town, meanwhile, were preparing for a more violent set of events, with one telling a freedman, William Jones, that “he would bet a good deal that Murphy would not speak in Camilla that day.”

Participants in the march were shot at and attacked as they marched through Camilla towards the Mitchell County Courthouse despite their peaceful intentions. The violence began when a drunken resident, James Johns, began firing into the bandwagon that accompanied the marchers. A white mob then began an assault on the marchers, including the town’s sheriff, who formed a posse to hunt down the freedmen. Philip Joiner was shot in the attack.

The local sheriff and a white-only “citizens committee” in the majority-white town warned the Black and white activists that they would be met with violence and demanded that they surrender their guns. In 19th-century Georgia, carrying weapons was legal and customary for Black and white residents. Marchers refused to give up their guns and continued to the courthouse square, where a group of local whites, quickly deputized by the sheriff, fired upon them. The deputized group of private citizens was by no means uncommon in many violent events against Black Georgians. Vigilance committees were common occurrences as groups of private citizens took it upon themselves to administer law and order through violence. In many cases, local officials and even the U.S. military ignored these violent forms of vigilantism, which were little more than a structured version of a lynch mob.

This Camilla mob’s assault forced the marchers to retreat into the surrounding swamps as locals hunted them down and killed between nine and fifteen Black marchers, wounding forty others. Nicholas Johnson writes of the massacre that “Whites proceeded through the countryside over the next two weeks, beating and warning Negroes that they would be killed if they tried to vote in the coming election.” (Negros and the Gun: The Black Tradition of Arms, p 90-92.)

Ramifications

Following the massacre, U.S. Army officer O. H. Howard, the Sub-Assistant Commissioner for the Freedmen’s Bureau in Albany, dispatched a physician to Camilla to attend to the wounded while scores of others came to the Freedman Bureau’s office in Albany. In a letter to Col. John Randolph Lewis, Howard wrote:

Col.

I hurry Mr Schlotfeldt off with the fullest accounts I can command of the affair at Camilla, I believe the account I send you, to be correct without any exaggeration.

I wished to come up myself, but I dare not leave the freedmen here to themselves. If any one can prevent them from going to Camilla en masse I can do it, therefore, I remain here.

Unless vigorous measures are instituted, and troops are stationed here for the protection of all parties, there will be much bloodshed. I cannot restrain the people.

It will be useless for me to attempt to block the way of thousands, for any length of time, I must protect my family and let the contending parties fight it out.

It is coming

I have sent the Doctor to attend to the wounded.

Respy & Truly Yours

O. H. Howard

The letter highlights the brutal circumstances of the massacre as well as the officer’s concern that with tensions high the freedmen themselves may rise up to seek vengance against the white vigilantes in Camilla, Georgia. (See original text.)

The Camilla massacre led to extended military occupation in Georgia, Congressional testimony and an affidavit by Assemblyman Philip Joiner on September 23, 1868. ( See original text.) However, little was done to change the prosecution of whites perpetuating political and racial violence against freedmen. The Freedmen’s Bureau conducted an investigation and others in the Army also conducted investigations confirming that Black Georgians did not intend to cause violence in Camilla but simply were there to attend the Republicans’ speeches. At no point after the event or the investigation did the U.S. Army dispatch any troops to Camilla to further investigate or prosecute perpetrators. Local Camilla authorities also took no action to investigate or arrest any individuals in the incident. The Camilla courthouse itself mysteriously burned down months after the massacre destroying the county’s records. (Warren Royal and Diane Dixon, Camilla (Charleston: Arcadia Publishing, 2008), 14)

National newspaper coverage highlighted the political and racial tensions of the incident and in one case called it an assault on free speech. However, the actual events were often confused as editors took their own editorial license in coverage based on their region in the country and their readership.

Despite the large Black demographic in southwest Georgia counties, the 1868 vote went to a Democratic victory as poll workers in Dougherty county for example, stuffed republican ballots into their pockets and conducted other means of voter fraud to assure a Democratic win. The campaign violence and election fraud perpetrated by white Georgians did end up achieving their desired result.

Camilla was one of many acts of political violence in the Reconstruction South and was certainly not the last one. Other riots and acts of election violence occurred in Mobile (August 1869), Baton Rouge (November 1870), Macon (October 1872), and in Colfax, Louisiana (Easter Sunday, 1873) when an armed band of Klansman entered the town, attacking and murdering Blacks. Political violence continued through the mid-1870s as white Southerners continued to use effective violence to suppress Black voters and Black political candidates.

Public Acknowledgement of “The Camilla Massacre:”

It wasn’t until 1998 that The Camilla Massacre became part of Georgia’s history. Camilla residents publicly acknowledged and commemorated the massacre on September 19, 1998, 130 later.

Special acknowledgment to Joshua William Butler for their thesis written about the Camilla Massacre. Titled “Almost Too Terrible to Believe”: The Camilla, Georgia, Race Riot and Massacre, September 1868, it can be read here.